Steve Koepp 0:00

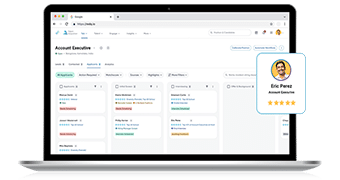

Hi, everyone. I’m Steve Koepp. I’m Co Founder and Chief Content Officer From Day One, our forum and corporate values. Welcome to today’s webinar, which is about the long term shortage of talent in the post industrial age and how companies can respond. Before we get started. We’re working with AARP to increase age inclusion in the workplace, and we welcome your help. So please fill out the short three question survey to let us know what your organization is doing or wants to do to support workers of all ages. If you go to the chat space, you’ll see how you can do that. Also, for today’s attendees, we have some complimentary VIP tickets available for one of our monthly virtual conferences. It’s coming up next month on Wednesday, December 13. That one’s about the arc of change for people and culture and 2024. Here’s what that one’s about. Recent history affirms that unpredictable events will buffer the workplace in 2024. But the trajectory of trends in 2023 gives an indication of how organizations will need to be ready for changing expectations among workers and other stakeholders. I’m putting a link in the chat right now to access complimentary VIP tickets to that virtual conference. The regular price for our tickets is $149. So this is a nice opportunity and I hope we’ll see you there. Now today we’ll be exploring the long term shortage of talent in the post industrial age and how companies can respond. We’ve entered an era where the shortage of workers, obsolescence of some skills and new levels of employee agency will present employers with historic challenges. Most companies are not ready. The new intelligence age is the time when skills employ creativity, information and AI will define our companies and will explore three strategies for success. Rethinking the organization is dynamic rather than static. Rethinking management with human centered leadership, and rethinking HR is no longer an expense center but rather a function like r&d that must build and invest in a company’s people. So these webinars presented with support from Eightfold and I’ll tell you a bit about them. Eightfold AI’s market leading talent intelligence platform helps organizations retain top performers, upskill and rescale their workforce, recruit talent efficiently and reach diversity goals. Eightfolds patented deep learning artificial intelligence platform is available in more than 155 countries and 24 languages enabling cutting edge enterprises to transform their talent into a competitive advantage. Now a few quick logistical items, and then we’ll get started. This webinar is being recorded and it will be available on demand soon after the event. So you can look out for an email in about 24 hours with a link. The same email will have info on how you can get professional development credits for this session from both the Society of Human Resource Management and the HR Certification Institute. You can look out for a written account of the conversation on our website from day one.co. And right now about 45 minutes into this webinar, we’ll have Q&A session. So you can submit your questions anytime using the q&a button at the bottom of your screen. Now I’d like to introduce our speakers in conversation. Today we’re pleased to have Josh Burson, one of the leading HR and workplace industry analysts in the world and the founder and CEO of the Josh person company. Joining us as well is Sonya Khan, the chief economist and head of market insights at Eightfold AI, a former senior economist for the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, and author of the new book, think like an economist transform your life by reshaping everyday decisions. Josh, Sania, we’re glad to have such deep expertise on half of this conversation. So welcome.

Sania Khan 3:51

Thank you, Steve. Good to be here.

Josh Bersin 3:53

Thanks, Steve. Excited to chat with you both. Okay,

Steve Koepp 3:57

Let’s get started. Traditionally, the supply and demand for talent ebbs and flows with economic cycles, but in a new report from Josh’s company that’s called Welcome to the post industrial age, which I have a copy right here. You’ve identified a more epic trend. Josh, could you give us an overview of what you identify in your new report? And, and then Sonya, you can follow up with your take on this kind of mega trend.

Josh Bersin 4:25

Sure, Steve, thank you. Well, so let me take a couple of minutes and just tell you what’s in the report. And I encourage you guys to read it. If you look at the role business plays in the economy and society. You know, if you go back a couple 100 years, businesses were collections of individuals who were working in teams in an agrarian merchant transportation economy, and we had a essentially linear business growth where the more people we hired, the more money we could make the more products and services we could provide. And then when the steam engine and the electric motor and other automation entered the workforce in the early 1900s, we had what we call the industrial hierarchy. So we built businesses around manufacturing, oil and gas, or distribution where we had machines. And the workers were essentially the labor to operate the machines. And then we built all of these companies, structures around functional hierarchies, management, telling labor, what to do labor being, in a sense, replaceable parts, which gave birth to labor unions. And we had essentially a surplus of labor. And if people left the company, we could find new ones, because we could relatively easily train them how to run these machines. But then along comes the computer age and the entire internet age. And all of a sudden, the industrial business models weren’t keeping up with the rapid changes in technologies and other services that were provided. And we entered this world where the only way you could differentiate yourself was time to market, the barriers to entry of an industrial company got broken down. So now the IP, and the rate of innovation and the rate of creativity or the customer service, became the company. And if you look at the company, think about the companies that you love today, it’s not just their machines, it’s the way they go to market, it’s the products they build, it’s the it’s the creativity they have the customer service, they have the design they have, those are human skills. So the value of the human went way, way up in the economic, you know, sort of machine that is accompanying. Well, while that’s been going on, we’ve also had the value of humans, and by the way, as AI becomes more and more prevalent, that’s going to continue going up. And we have an interesting chart in the report that shows that, at the same time that’s happening, the number of humans available to work is starting to go down. Because we have baby boomers retiring, the fertility rate is below replacement in virtually every developed economy. Japan, Germany, UK, most of the developed older countries are now shrinking their working population, and the demand for new skills is going up and up and up and up, because the rate of change is so fast. So we’re basically sort of in this, these curves are kind of moving in the opposite direction, where we have more and more IP and business value by humans and, and less and less sort of surplus humans in the workforce. So we’ve got to treat people better, we’ve got to move people around better. That’s essentially the big story here. Now, what you do about it is three things that Steve mentioned. We can talk about that later. But that’s the quick and dirty story.

Steve Koepp 7:53

Sania, do you want it just from the point of view of a labor market? Economist? Can you tell us a little bit more of how you’ve observed this sort of thing? It sounds like a decommodification? If that’s the right word of the worker into something different?

Sania Khan 8:06

Yeah, so I’ll take a slightly different approach to this question. But really, if you look at the supply and demand of workers and the labor force, it’s absolutely different from what we’ve seen in the past. You know, usually, when you have interest rates rising, and you have inflation rising, it’s going to affect business’s bottom lines, and therefore affect, you know, a pullback in the labor market. And what we’re seeing instead in this case, and what we’re likely to see in the future, is, there’s still going to be a strong labor market. And employers still want employees, there’s, you know, because of an Josh mentioned this in the report itself, but because of, you know, an aging workforce with baby boomers retiring, and then, you know, decreased fertility rates, you know, more people out of the workforce, and losing the skills of the future, potentially not resizing and upskilling themselves. where employers are at a loss of employees and the labor is in high demand, and it’s likely that this is going to stay for the future.

Steve Koepp 9:29

Well, thanks, Josh. Was there an epiphany or kind of a turning point in your research and your company’s always doing research that inspired you to call out the scarcity of talent is one of the biggest challenges that’s out there for companies?

Josh Bersin 9:42

You know, I’ll tell you this, the way that we came to this, you know, as soon as very well. The typical equation that you learn in business school about the labor market is when the unemployment rate goes down, the inflation goes up. When you reduce inflation and you slow the economy, the unemployment rate goes back up again, because we have surplus workers. So you know, I’ve watched that cycle for years. And you know, there’s all these charts of how it’s gone in the past. But over the last four years or so, from the pandemic on, because we talked to so many companies, we heard the same thing over and over and over again, we don’t have enough people, we don’t have enough skills. Retention is a problem, we don’t know where to source them, people are leaving. And then you look at the effect of this, you know, sort of highly empowered workforce has, and we have employees saying, I’m going to quietly quit, I’m going to work my wage, I’m going to do what I need to do, I don’t care what you say, you don’t like hybrid work, tough luck, I’ll go find a job where I can work remotely. This is a completely different situation. So as I looked into it, and I looked at all the data, if you look at the World Bank, they have all this information on the future demographics of different countries. And you find out it’s really surprising, but every major country is going to peak in the working population in the next decade to 15 years. So economy aside, and I think there will be economic fluctuations for sure. I think this is a long term, excuse me secular in that sense, trend that we’re going to just have to deal with, and I see this going on. And I think a lot of companies think well, you know, we’re just going to put more money into recruiting, and we’re going to spend more money on wEightfold, or whatever it may be, you got to be smarter and smarter and smarter about finding people and taking taking care of the people, you have to really grow your company. One more point, Steve, you know, if you think about, you know, sort of that problem of not having enough people, you know, the solution to that is not working harder and harder and harder to hire. It’s making the people in the company more and more productive. And so there’s this other countervailing sort of narrative, that, you know, most of us were trained that the way to grow the company is to hire more people. Well, I don’t think that’s going to be true, I think that’s going to be a piece of it. But we’re going to have to look at ways to upskill people, move people into better jobs, automate and improve business processes. And that’s really the world we live in. And that’s what the story is all about to me.

Steve Koepp 12:28

Well, and in a real life example of that it sounds like you know, the tech tech companies during the pandemic just went crazy hiring and oops, that does not mean that was not a path to higher, higher profitability, I guess. By the way, we’ll be putting a link in the chat space to Josh’s report at the end of the webinar, so you can all get access. But first, we have other things to cover. Sonia, could you tell us what are some of the early warning signs or symptoms of the challenge? We’re going to be facing labor shortages in different industries that might be kind of proving the case in small ways.

Sania Khan 13:05

Yeah, I think you nailed that. Nailed it on the head. Is that the right phrase? skilled labor shortages are what we’re going to expect for sure, especially in areas like health care, specifically with nurses with technology, green technology in particular, I know semiconductors is some work that we’ve done on and it’s likely that with all these new technologies, the people will need to be upskilled and re skilled in this rapid evolution of new technologies and specialized skills, will need to be attained. And, and that’s okay, right, because I think companies now will need to focus on their employees and will have to focus on the rescaling and upskilling of their employees. So that is something that we’re going to be looking at. In addition, we’ll be looking at, perhaps higher turnover rates if employers don’t focus on their employees. So we’re seeing that with retail, hospitality, customer service industries that we saw, especially during the pandemic. And in the latest jobs report from the BLS in October, we saw that these industries aren’t hiring, like hiring increased buttons, it was not across all industries. And so we’re seeing the ebbs and flows and increased employee turnover in certain industries as well.

Josh bersin 14:44

Can I point out one point here. Yeah, yeah, there was a report. I know you used to work for the BLS. There was a BLS report that came out just a couple of weeks ago on occupational growth over the next decade. And I think they said that 54 percent of the new jobs that are expected to be created are in healthcare. And that is the number one employer in the United States, and it is growing as a percent. So one of the other things we’re dealing with is, you know, we’re all living longer. But we’re not living longer alone, we need a little bit of help. I mean, whether we’re aging or not, we’re living, you know, many, many more years. But you know, we gotta go to the doctor more often, there aren’t enough doctors, all the medical facilities are getting bought up by private equity companies, they’re all combining, there is a huge shortage of clinical professionals. So whether we, you know, want to hire AI engineers, or software engineers, whatever, there’s this huge population missing in that segment, that almost dwarfs everything else. So, you know, every industry has their shortages, but that one is just massive, and it’s gonna get worse.

Steve Koepp 15:54

And you mentioned so many relevant industries that assisted living will be a big thing, and that a lot of that work has to be done in person, it can’t necessarily be automated. So those people will probably get paid more too. So but does this all, either? Does this all go away? If we have too much to talk about but slow arriving? Recession? Does that change things, Joshua, an illusion to the business cycle?

Josh Bersin 16:20

You know, I’ve been trying to get a hold of Paul Krugman or one of these big shots, you know, guys to see if they’ll talk to me about it. And I’ve talked to Peter Coit, The New York Times about it. Um, yeah, of course, if we have this match, if we have some sort of a massive recession, there’ll be unemployment. But first of all, it doesn’t look like we’re going to have one of those. But I don’t think that changes its long term issue. And I don’t think CEOs and ch heroes should run their companies expecting there to be a certain type of an economic environment, they have to run their companies for the long run. And they have to just, you know, kind of think about this issue, because as a corporation, I can’t wait for a recession to hire people. In fact, that’s the time I don’t want to hire people. So I’ve got to figure out a way to plan for this, this sort of environment that I live in. And that’s really, you know, the way I see it, so I think there’ll be blips, but I don’t know, on Sunday, unless you disagree, I think this is a long term issue. Agreed.

Sania Khan 17:17

It’s definitely a long term issue, unless somehow we open up immigration drastically. I know that was curbed during the pandemic, and it’s starting to pick up again, too. But it’s really that, you know, there’s all of these openings. Businesses want to do more, they want to come out of this pandemic. And they’re, they’re really in this mode of innovating more across departments. And how do you do that without the people there. So in one way or another, whether it’s like AI to assist people, or it’s getting more people through the doors by being more flexible, and having better policies, workplace policies, all of that stuff, that’s that that’s going to be the key, I think, in the future.

Josh Bersin 18:11

Yeah, and just one thing on workplace policies, I mentioned the state, tomorrow, we’re gonna introduce a big research report, we just finished the four day workweek. And you know, believe it or not, it sounds wacky, but this is becoming a big deal. And not just, you know, because people want to go home on Friday and go to the dentist, but because employees want flexibility. And we’re actually finding that this particular idea creates job productivity, and job forces companies do job redesign. So there are things that we’re going to do that seem unnatural now to deal with this shortage, that are going to be commonplace in the future. And that’s just one example to me.

Steve Koepp 18:56

Now, does that mean now when you say the four day workweek, you don’t mean doing five days work in four days?

Josh Bersin 19:01

There’s a distinction here. It’s interesting. It’s really interesting. You guys should all read up on this. It’s called work time reduction. And what’s been going on is a long time ago, and I don’t know why in the last 20 years companies tried four days of work for four days for five days of work. And people got burned out and didn’t really work out. So this new idea is, let’s keep the company businesses the same. Let’s pay people the same wages that would tell them they have 32 hours. And you know what they do? They get rid of the junk work they didn’t want to do anyway, they get more focused, they stop going to stupid meetings, they spend more time thinking about what they’re accountable for, and they end up getting more work done. So you know, anyway, I don’t want to get too off that topic. But to me, that’s an example of the kind of thing that sounds strange that we’re going to do more of in this new economy.

Steve Koepp 19:57

Do you think either one of you thinks that it could actually be kind? Another motivational development for people to embrace technology to get the boring work done and like, Okay, I have to invest time to learn this, but it’ll help me get out on Friday.

Sania Khan 20:10

Yeah, exactly. I think I am coming out with an Inc. piece later this week or next week, and I will talk about how working parents, I’m a new parent myself, and how you really have to be cautious of your time, and you end up learning to do more in less time, because your time is limited. So in actuality, you’re more productive. And, you know, just from an econ point of view, how do you really define productivity? And, you know, in the textbooks, its output per worker, which is like, how many trinkets can you make in an hour. But then if you think about it, in today’s day and age, I think it’s, it’s a revenue per employee. And that’s a way that service, or corporate settings, can really look at how effectively the company is utilizing its human resources to generate revenue. And so I think that will be a key to determining for employers to see if this four week four day work week will work. And again, it’ll be a sign that you can compare with competitors. And like old management, where, like we said, hiring more people isn’t necessarily more productive. It’s how many people it’s how the people you have, how productive they are.

Josh Bersin 21:42

On the topic of productivity, there’s kind of two sides to productivity, there’s the individual becoming more productive. And if you think there’s a hilarious video, you’re gonna see on the website that I’m posting tomorrow, of a very, very, very famous tick talker, who started a theme called lazy girl jobs. And it’s a hilarious video about how she gets all our work done in two days. So she can take her dog for a walk, and she doesn’t tell her boss that she’s using all these AI tools to do all this work. And then there’s organizational productivity. And that’s really where we come in, is how do you organize the company, and, you know, move people around and plan roles and use technology. So you’re not just hiring, hiring, hiring, because as Sonya said, the sign of a poorly run company is low revenue per employee. It’s right now that’s a sign of a company that’s basically going to be at risk in a sense. And that takes engineering change management. And one of the things we did, we’ve done all this research with Eightfold in different industries, is the companies that are really good at improving productivity, by the way, including healthcare companies are very good at Human Resources. They’re good at training. They’re good at facilitating workshops, redesigning jobs, flattening the corporate hierarchy, changing the role of leaders, democratizing it, democratizing training and career development. These kinds of touchy feely things that felt nice to have maybe 10 years ago, are sort of critical now to becoming more productive in this new economy.

Steve Koepp 23:27

Which I think connects to another question that I had, which is, in the you, Josh, you touched on how we got here in terms of the agrarian age, industrial age. But what are some of the early you know, the sort of information age ways that workers and leaders were developed and how did those pipelines change and evolve?

Josh Bersin 23:49

Well, I mean, the big the big shift, that’s, sort of underneath all this is this shift from what I call from jobs to work. In the industrial model of companies, which we all live in, there was a job title, a job level, job description, and it was basically a box. And the reason it was created was that we can swap people in and out of that box. And that is all and the leftover artifact of industrial bits actually comes about, by the way, it comes from slavery, actually, the slave trades operated like this. Well, now we’re in a sort of company where the individual skills are used for many things. They may be in a role or a job title, but in a given day, or given week or month. They’re doing many, many things besides what might have been written down in that job. So these rigid job descriptions and job titles and job hierarchies are getting in the way of reorganizing and redesigning the company to be more efficient. So and this is, by the way, one of the things eightfold does really helps people within this tool for organizational intelligence, but is simplifying all of these old job artists. AX, so people can move to new roles more quickly. There’s a lot of resistance to that, you know, managers don’t want to give up their job titles, they don’t want to give up their levels, they don’t want to give up their corner offices, etc. But that’s getting broken down more and more and more. And that’s just sort of an existential change in the way companies are going to operate, certainly over the next decade.

Sania Khan 25:23

And just to add to that, I think going from job descriptions to skills based, you know, work will be the future. So really looking at, you know, if you’re looking at talent acquisition, you’re looking at what skills do I want from this person or the ideal candidate today. And then yeah, maybe you’re not finding that out there. But then you look at adjacent skills and how people can be upskilled and rescaled, to get to what you want, and that opens your pool significantly. And that’s something that eightfold really does really well. And I think we have a really really good system in place to show how adjacent skills are from one another. And, you know, you can do that with ta you can do that with TM, there’s so many ways to look at skills this way. And it really opens up, I think the future what the future of hiring and looking at your workforce will really look like the

Josh Bersin n 26:29

example this because I have a very specific example. So one of the first studies we did with Eightfold was in healthcare, where there’s this massive shortage of clinical professionals. And what they now do in healthcare, where nursing is usually the critical talent issue is they look at what a nurse does. And if you’re taking out the trash, cleaning the floor, scheduling another nurse filling out prescriptions, that’s not your job, you’re over-skilled for that. So they take that stuff that’s getting in the way of you doing nursing work, which you’re paid to do, which they call working at the top of your license, and they either automated or they find other people to do it. And they only can do that. And companies can only do that if they look at the skills needed in these different roles. So as Sania said, as we become more skill centric in the way we run companies, your jobs are not going to mean the job titles not going to mean as much. I mean, I remember interviewing an engineer and software company a couple years ago, in San Francisco, and they’re going through this issue where one engineer is stuck over here, and he can’t go work on this because his boss won’t let him go. And the head of HR said, we’re doing away with that. All of you engineers have a new job title, engineer, period, you’re all fungible, you can work on a lot of stuff, and we’re not going to lock you into this group or that group anymore. And I think that’s gonna be the way you know, companies are gonna have to deal with these issues. And it’ll be good for people too because workers and individuals can just do more with their careers over their lives when they have this flexibility.

Sania Khan 28:07

Yeah, yeah, just sorry to interrupt. Just another point on that is, if you take if you break down the hierarchies, and you really look at the skills that an individual has, and you look at the needs of an organization, you can kind of put employees in specific, goal centric projects, like kind of like consulting does, instead of just having you siloed to one department, you can now move around to where you’re needed based on your skills. And I think that is a great, like future idea for companies, because employees would also get the most benefit, and companies would be able to really have employees that are well versed in the book and the whole enterprise.

Steve Koepp 29:00

I just the question I was going to ask as a follow up was, as the skills proliferate, that taxonomy of skills that are needed and how much they’re needed, and how they rise and fall would seem to not only take computational power to sort those out, but constant inputs, right. And updates. Is that a factor of machine learning or something just in your particular company?

Josh Bersin 29:21

Well, this is sort of the miracle of products, like a fold, you know, people used to think so the old way of thinking about skills, we had this thing called the competency model. And we literally did it by hand, and we wrote down all the competencies and we put it in a book and then we said, okay, lock that and let’s just say, Okay, we’re done. Let’s go do something else. This is different. This is a constantly changing, never ending sort of data system. That’s figuring out what the new skills are. And, you know, if you look at a new domain like AI, I don’t know all the hundreds of skills under AI I’m not sure anybody does. I think you need AI to know what those skills are. And there’s going to be new inventions every day. And so what we can do with tools like eightfold is we can start to look at what are the trending technologies or business practices or domains or functional areas that are growing in our industry. And we can say, You know what we either do or don’t have people that know that stuff. So let’s get some development to move into that direction. Or maybe we’ll hire some people that we can find that know more about it. And that’s just a level of intelligence we never had before.

Sania Khan 30:33

Yeah, it’s, it’s pretty phenomenal. They’re using AI and machine learning, in order to look at these skills. So you bring in all these billions of data points. And it’s, it’s pretty neat, because you can tell, you know, what a software engineer at Google does has a difference and how a software engineer has at Facebook and you know, their skills are actually different, because the algorithm knows exactly what they’re working on. And therefore, what their skills are. So yeah, getting rid of the titles and really looking at what you’re actually doing. And what you’re skilled at is

Josh Bersin 31:15

Another sort of interesting example is Chevron, which, by the way, also uses Eightfold. So, so Chevron a couple of years ago, we helped them with some stuff where they were trying to figure out what skills they needed to get into battery mining, mining of materials for batteries, solar energy, natural gas, they already understood, so they have petroleum engineers, and various different kinds of manufacturing refinery and so forth. So they said, let’s call it an energy engineer. What the heck is an energy engineer? I mean, that is that you know, I studied mechanical engineering in college thermodynamics. So they went through and they posted a bunch of jobs, but nobody applied. And they thought, well, we gotta get smarter with this. So after using Eightfold, and some other tools, looking at some data, they figured out what were the funk sort of scientific domains they needed to hire, to fill these jobs and there because there were no job titles that even defined what the jobs were. And now they’re filling the roles and they know what they need. But if they didn’t have those skills, intelligence, they wouldn’t have been able to fill those roles.

Steve Koepp 32:24

Sonya let’s talk about demographics. For a moment, things are changing fast. In terms of workforce participation, people like me are baby boomers. We’re, you know, our line chart is going down and folks like my two sons, their Gen Z people are going up. Lines are crossing, what kind of trends like that you see, how will that affect the fact that labor shortage,

Sania Khan 32:49

I touched on this briefly, but we’re seeing an aging population, we’re seeing declining birth rates. And then we’re also seeing a shift in skill requirements, too. So, you know, it’ll be more important than ever before, to have to focus on lifelong learning to have multi-generational workforces in the workplace. Right. So I think it’s important that if, you know, an experienced worker wants to continue to work, employers should look at their skill sets and try to hire them, because they do bring a lot with them, and a lot of knowledge with them. And that diversity in terms of age will really set those employers apart. And then on top of everything else, I think there’s also going to be policy and workplace adaptations that we’re going to need to reconsider and rethink about, like retirement and pensions, age friendly workplaces. And yeah, and then, for everything, like everything I just talked about, there’s going to be economic implications for all of that. So on productivity, and then innovation and automation and all of that.

Josh Bersin 34:13

You know, in other words, Steven that questions real quick, you know, another thing that’s really changing that I don’t think people think about enough is the economic model of the of, I’m a baby boomer to was you go to college, you get your degree, you got your skills, you go to work, you do it for about 30 years retire. Now, you live to the age of 100, or 110. You work for 60 years. Your college degree is ancient history. I don’t even remember what I did. I’m not sure it’s even relevant. In fact, I need to go back to school about five times during my career to keep up. That’s a completely different economy. And the educational institutions haven’t figured out what to do yet because they’re worried that they’re not going to have Have kids. So you know, one of the other things has changed is lifelong education. And companies are, you know, pouring money into programs and certificates and education and l&d to try to deal with that. And that’s a totally different way of thinking about careers and the economy and the workforce as well.

Steve Koepp 35:21

I think what we could talk about now is what leaders should do? How should they think differently about how organizations are structured? We’ve touched on this a little bit, but you know, how, how well, we can talk about workforce planning because Joshua, we have to share that as a mass on. So we’d like to know about that. And I’d love to get your take on it, too. Sonya,

Josh Bersin 35:45

Let me talk quickly about leaders, there’s a couple of questions about employee development and careers, too. So one of the pieces of research we just published that came along with the post industrial age sort of kit, was what we call the irresistible leadership. And, you know, there’s probably 50,000 books on leadership and tons and tons of IP out there and lots of courses and stuff. But the big thing that’s changing is, leaders have to understand this, this shortage, you know, existentially, and operate in a company where transformation and growth isn’t an episodic thing. It’s never ending. So it used to be, you know, you were kind of in a job, and you were measured by your ability to execute and hit the numbers and whatever. And then every now and then there was a transformation, then you go back to your job. Now, everything’s transforming on a continuous basis. And so the new model of leadership is, can you build a company that can move people around, that can develop people that can hold people accountable, but also give them the opportunity to move when you need them into a new place? Those are different kinds of leadership skills, as you know, Jack Welch had a GE, in the air, those kinds of books. So, there’s a totally different kind of leadership, sort of mindset. The other issue on leadership is, when you have a flattened organization, you don’t need so many leaders, you don’t need so many levels. So everybody becomes a leader. And we’re all working on cross domain projects and different initiatives here and there. Sometimes I’m a leader, sometimes I’m a subordinate to somebody else who’s leading a project. So we have to democratize the concepts of leadership to more people, you know, people my age, Steve, you’re probably around my age. I mean, we measure our success by how you know, would I ever get promoted? You know, and if it took me 10 years to be promoted, I felt like I was falling behind. Well, that’s not really going to be the model anymore, either. You know, maybe your growth is going to be by the level of skill you have and the level of contribution you make. And maybe the amount of money you make, and your level may not ever change, it may never be that significant, maybe you won’t need to have a whole organization working for you. So there’s a lot of interesting changes in leadership and leadership development that are part of this.

Sania Khan 38:13

Just one other thing. Great. Yeah. Along with this talent, mobility is something that I think we’re going to see more of individual contributors, like Josh just mentioned, we see this intact at the moment. And what they really do is, instead of managing others, or focusing on their own work, and we’re probably going to see more of those people, people will have instead of moving up the ladder, there will be no ladder, it’s going to be Yeah, what what areas of the of the company, have you worked in? What holistic picture can you bring to the table, your skills, your ideas, your appetite for innovation? I think all of that will be really important.

Steve Koepp 38:59

And how should shifting from leadership in general to specifically HR and a lot of people in our audience, our HR leaders, be different in different disciplines? How should HR be different from being a cost center, an administrative center to something more like planning, development, things like that? How can that evolve? Well,

Josh Bersin 39:21

This is a huge topic. And this is another big study we’re launching the week after next. So we’ve been working on this, of course, with lots and lots of companies about their HR functions. And there’s a couple of big changes that are happening there. And everybody’s going through little pieces of this. The history of HR, of course, is that HR was the administrative function that managed the hierarchy and the bureaucracy and the industrial organization, and it was the compliance function, and it was the function that managed PE and some of the fundamental legal issues. Well, now that we’re a talent driven company, and a talent short sort of environment, HR has got to do a whole bunch of different things. It’s got to understand where the skills are, where the skills are going. It’s got to focus on building skills, they have to interconnect the silos of HR. One of the things that happened to HR is that HR got sort of inadvertently designed around what I call the 1980s. IT department, we have a group over here that does diversity, we have a group over here that does recruiting, we have a group over here that does pay, there’s a group over there that does something else they don’t, they’re kind of all little COEs, that’s all gotta get interconnected. You know, the HR professionals themselves have to be cross trained and upskilled. You know, HR people are very smart, hard working people, they want to understand AI, they want to understand or design, they want to understand pay equity. If they’re not in the pay group, that doesn’t mean they don’t need to understand it. So there’s cross training inside of HR, we call this systemic HR, which is thinking of the HR function itself. Like it’s a big professional services organization, with services and technologies, but also able to move and initiate new projects and bring groups together to work on challenges that come up in the organization. And, you know, my experience with HR people over the years is, they’re itching to do this, because they’ve, I mean, we used to talk about the fact that HR didn’t have a seat at the table, because nobody would listen to what the HR people were saying now that the CEO is saying, hey, you know, you over there, and HR helped me fix this skills thing, reorganize the company, and adopt AI for me work with it. And all of a sudden, the HR people thought, wow, okay, so there’s a lot of stepping up going on in HR. We call this systemic HR, because it’s really thinking of HR as a system, with lots and lots of skills and capabilities that can be deployed in different ways, in companies, and it’s a very exciting time, you know, for people like me that are in this domain. Well,

Steve Koepp 42:02

it’s very, it seems like a very forward looking just, you know, I grew up on a fortune 500 company, HR was usually associated with conflicts and problems, what happened, and this is pitching in a different direction, and what will seemed like a great way

Josh Bersin 42:17

of workforce planning, he just mentioned, and I’ll turn it over to Sania. So you would think that with all these shortages and skills issues, that workforce planning would be a central issue, it actually is a part of HR that is very much behind. It’s, in most companies, a headcount planning budgeting process. And so I think, you know, over the next couple of years, companies are gonna get a lot smarter, about skills to skills based planning. If you look at, for example, in the aerospace and defense industry, where the companies, the big companies like Lockheed Martin and Boeing, they’re very dependent on the skills, they have to meet the needs of billion dollar government contracts, they don’t wait for a government contract to come and then go hire a bunch of people they are, it’s sniffing around all the time, trying to figure out what skills they’re going to need to address the next big procurement. Most companies aren’t very good at that. And so this idea of skills based planning and skills based workforce planning is definitely going to become part of the whole new domain.

Steve Koepp 43:28

So do you want to add anything? And then I think we’ll go to our audience questions, you’ve got a bunch of excellent ones. Sure.

Sania Khan 43:33

Yeah. Two things to add. So one, on the HR front, that you asked about earlier, I think HR will want to and will need to be more strategic. So being more actively involved in business planning and aligning HR strategies with business objectives, like John mentioned, they’re now being asked by the C suite for these things. And that really, I think, means embracing technology and data analytics. So how can you use data to predict workforce plant workforce trends, or for TA for TA TM, for performance? How can you use data and everything that you are thinking of today, and for the future, and for your advantage, right? And so I think that’s where, like Eightfold, and I’m a little biased here, but that’s why a fold is really great at what we do and what we can help with and how like you can bring not just the data from your own company, but from millions of data points and make better decisions with it. So just wanted to add that and then, in addition, in terms of the Boeing example that you gave another A point of research that we did recently was at Eightfold was looking at when airlines had laid off their workforce, all of during the pandemic, all of the skills that they lost during that time was significant and then trying to hire back those people, but they had already moved on to other industries or other jobs. It was a, as you all have probably seen a catastrophe when, you know, rebooking systems and flights being canceled and not having those customer service representatives that knew what they were doing. So, you know, like, from the beginning, we talked about when you do have a surplus, or think you have a surplus of employees and you and you lay them off, it’s not necessarily for the best when you leave, when you lose those crucial acts, experience and knowledge as well. So

Steve Koepp 45:59

just a point, yeah, and we just have proof of your point, we just have, I think the busiest travel day in US history and airlines just came roaring back and eating every single person. You

Sania Khan 46:10

Now, on the topic of layoffs, there’s been a lot of studies done that show that companies that go through massive layoffs end up losing more money than gaining in the long run, because the recovery process is so difficult, sometimes they go out of business too. So layoffs,I think it was a Harvard Business Review study that said even though you might accompany might think it’s a cost effective way to reduce, you know, reduce their bottom line or help their bottom line, it ends up in the long run actually hurting them because of employee morale of those who stayed and, and, and all that reputational distress as well. So

Steve Koepp 46:55

alright, thanks. Well, let’s go to some questions from our large audience. Hannah asks, With the increased utilization of AI to improve employee efficiency. What are your thoughts on navigating the potential biases embedded in AI? And I think Sonya is probably something your companies thought about a lot. Yes, yeah,

Sania Khan 47:15

Thank you. Um, so Eightfold is doing a great job with this. I’ll give you an example with talent acquisition at least. So you know, you are looking for the perfect candidate, you are trying to be as diverse as possible here. And the algorithm really tells you how to pick the most diverse candidate. And if you, for example, are a woman and you don’t meet all of the bullet points in a job description, you’re less likely to say that you’re going to apply for the job. But then if you’re using, if the company you’re applying to is using eightfold, it actually tells you like you would be a great match for this job. And that increases more applicants and increases diversity that way. On the flip end, you know, if you’re a recruiter, it helps expand the talent pool, and really zero in on who you’re looking for. And, and with the skills, expanding skills, you can expand your talent pool as well. So all around, it’s just doing great stuff for di, you know, just on that issue of bias. I mean, the reason that eightfold is able to do that, by the way, is because it’s amassed a huge amount of data, and it has basically a giant sample of human beings to look at the risk of AI having a small data set that actually is biased. So when you start building your own AI systems, and using AI on some of your own company data, it’s going to be biased based on the employees you have, like if you ask your you know, internal system, like Workday, who’s likely to be promoted, it’s gonna look at all the people that are promoted. They’re all white males, and it’s going to look for more white males. So that’s where the risk is, is not having enough data and really, and that’s why, you know, a fold is so successful at this.

Steve Koepp 49:26

All right, well, thank you both. Another member of our audience, Dawn asks, What do you see as the implications of the trending pushback or rejection of traditional employment arrangements? For example, should organizations prepare to have larger contingent labor populations, permanent external operation partners and so on? What’s your future?

Josh Bersin 49:49

I think this cat’s been out of the bag for a long time, but I don’t think people realize it. 40 to 50% of the American workforce is contingent now. So it’s one Much bigger than you think. And even when you go into big cuts, you go to pharmaceutical companies, tech companies, significant numbers of their workers or contractors are outsourced to other agencies. So yes, this is a huge trend. I think the reason that maybe HR people don’t see it is we don’t tend to manage that part of the workforce, we don’t see it because that part of the workforce is oftentimes in a procurement system. But that’s got to come in. So there’s a trend for more and more functionality of the contingent workforce to be in the HR tech stack, so that the company can manage the contingent workforce as carefully as they can manage the full time hourly paid workforce.

Sania Khan 50:42

And just to add to that, my team at Eightfold actually did a forecast of contingent workers. And we saw that we did this in 2022. And we saw 2023, it’s going to be an increase of 53% of contingent workers globally. 2024, would see a 34%, increase 2025 and see a 25% increase, and then 2026.

Steve Koepp 51:12

We’re all going to be contractors.

Sania Khan 51:14

Yeah, so it’s, it’s on the rise. And we think that because of economic uncertainty, so will employers be choosing these contingent workers over full time employees, and then also how jobs and contracts and the future of work might look like you might just want someone for a specific period of time to fulfill a role or fulfill a need, and you might not need them for for longer. So that’s what we’re thinking.

Steve Koepp 51:48

Now, we talked briefly about the flatter organizations of the future where you don’t need as many managers or audience member to Aparna I hope I’m pronouncing that name correctly, it says, it asks in a flatter organization, where promotions are changing titles were much appreciated in the past, but no longer available. Now, how do we give people a tangible sense of career progression or advancement?

Josh bersin 52:12

Let me tell you about that, because I’ve been through this. So I had the experience of working for Deloitte for seven years. And in a sense, every company is becoming like a professional services company. And the way it works in a professional services company, is you don’t get a new title or new level, you get promoted and your pay based on the contribution you’ve made. The reputation you have, the skills that you’ve delivered, the projects you’ve achieved, and the people that ask for you to work with them on new things. That is the way we should be rewarding people, not on Oh, I got myself to this level. So doggone it, I’m not moving and you’re not getting my slot, because I’m hanging on to it with both hands until I retire. That is the old industrial model, it gets in the way of all of these changes we need to make. And it turns out in that kind of sort of organizational model, it’s very exciting, exciting for people, because they get to work with other groups, they get to do different projects. Usually there’s a career advisor, or a manager or coach that helps the person. And you can have a magnificent career and an organization like that, and you can still reach very, very high levels of contribution and span of control if that’s what you want to do. So it’s really a change in reward system and a change in sort of storytelling. You know, in the old days, you know, the storytelling was, oh, you know, someday you’ll have the corner office someday you’ll have the special parking space, someday you’ll have the company car. We need to kind of let that go. Yeah.

Steve Koepp 53:53

Here’s a question. Interesting question. From Jamie in the audience, the competitiveness of the future labor market would seem to apply only for the subset which acquires the skills and keeps up. Is the future then ever increasing inequality across wages? Will that get worse enough to risk social stability? Well, that’s a but the one thing leads to another perhaps, but is there going to be the skilled and the not as skilled and increased divide?

Sania Khan 54:23

I can take this one. So I think we might see two different ways of looking at it. So we might see the skilled Tech of the skilled workers that will need to get up skilled and if they don’t get upskilled productivity will lag and you those people might not move into the future careers of the future and future needs of the employer as well. And then there’s the other I don’t want to call them lows. killed because that’s not what they are. But maybe those workers that might be skilled in plumbing or apprenticeship programs or things of that nature, and so those are going to be in high demand as well, because an AI can’t take over those jobs. So what we might see is a convergence of labor, and those are the two areas where labor will be important and will be needed. And if we don’t get those, those people on, on the one hand, who are doing all the plumbing and, and whatnot, like the mechanical skills, then we, you know, they’ll be in higher demand and have higher pay as well.

Josh Bersin 55:48

Yeah, my perspective on this is, you know, I think we’ve reached a very high level of inequality in the United States right now, for a whole bunch of reasons, tax laws and some other things. And I think this, I don’t think it’s only because of the skills shortage. I think there’s other reasons there’s, you know, race, race, racial issues, and so forth. And, you know, discrimination and diversity and so forth that have caused that, you know, my positive thinking on this is, because of the more mobile mobile, sort of job models we’re going to have inside companies, we’re not going to force you to have a college degree with a computer science degree from Stanford, to get a job in software. Now, if you don’t want to educate yourself, and you don’t feel like you have the capability of being a software engineer, fine. You want to be a nurse, you want to work in a hospital. I mean, I think there’s going to be more opportunities for people that don’t necessarily have these pedigrees. And honestly, I think the situation for under-skilled people is going to get better. But given the fact that careers are longer and lifetimes are longer, people that don’t want to re-educate themselves are taking a risk. You know, even a plumber, who doesn’t know the latest technology, and plumbing isn’t going to be a very good plumber. So I think they’re, I think this and the government spends a lot of time and money on this. And I think we’re just gonna have to continue to provide a lot of education opportunities for people so they can move to the direction where the labor market is going.

Steve Koepp 57:26

Well, we have time. Thank you. Thanks. We have time for one more question, as it kind of derives from what you just said, which is, one of the parts of this conversation is determining whether people actually have the rapidly evolving skills required for work. So how big should enterprises tackle the accreditation of people skills at scale, and a pay. So we’ve done webinars on credential, and there’s so many, you know, any quick take on that?

Josh Bersin 57:56

Well, we do a lot of research on this. And, you know, I think there’s two things companies have to do. Number one, they have to have a philosophy, deep down in their hearts, that every human being can do more. And then if we give them the opportunity, they are capable of doing it. Because some companies don’t have that, some companies think if you’re stuck over here, that’s it, you’re never gonna make it over here. That mindset has to go. And then the company just has to invest in tools, and programs and support for education, training, skilling skill systems like Eightfold, because that investment pays off in the productivity and the growth of the people you have. And given that it’s hard to hire somebody on the outside, by the way, I have some research that shows that it can be six times more expensive to hire a highly skilled person than to develop them internally. That money should be available. Because you’re counterbalancing and against a very difficult job of hiring people. So to me, those are the two issues.

Steve Koepp 58:57

So we have a half a minute left. Yeah.

Sania Khan 59:01

And I think just to add to that, we have something called a skills portfolio. And I think the number one thing that companies need to do when we ask them when they work with us is really what is your department’s need? And what is your organization need? And break it down into? What are those actual skills that you’ll need for the future? And then let’s take a step back and look at it from big picture to small picture. And then what skills do you have in your workforce? And then how do they align up? So I think it’s, it’s not just oh, these are the 10 skills of the future and let me just rescale people but really being methodical about where those people are going to be working and what departments and for what need

Steve Koepp 59:52

Right, well, I wish we had more time. Sania, Josh, thanks so much for sharing all these thoughts and research and, and great tips. For our audience, thanks to Eightfold for your support. And to all of you who participated today, you’ll get your S HRM code in email in 24 hours. So on behalf of all my colleagues from day one, thanks for participating and staying well. Bye for now. Thanks bye bye